Welcome to the bookshop! Making books with artists is central to the Carpenter Center’s mission.

Our publishing program complements our commission-based curatorial program, with a focus on new scholarship and texts, and an artist-involved design process. We publish a few books a year, and release a new tote bag design annually, so please check back for new totes and titles!

Publications

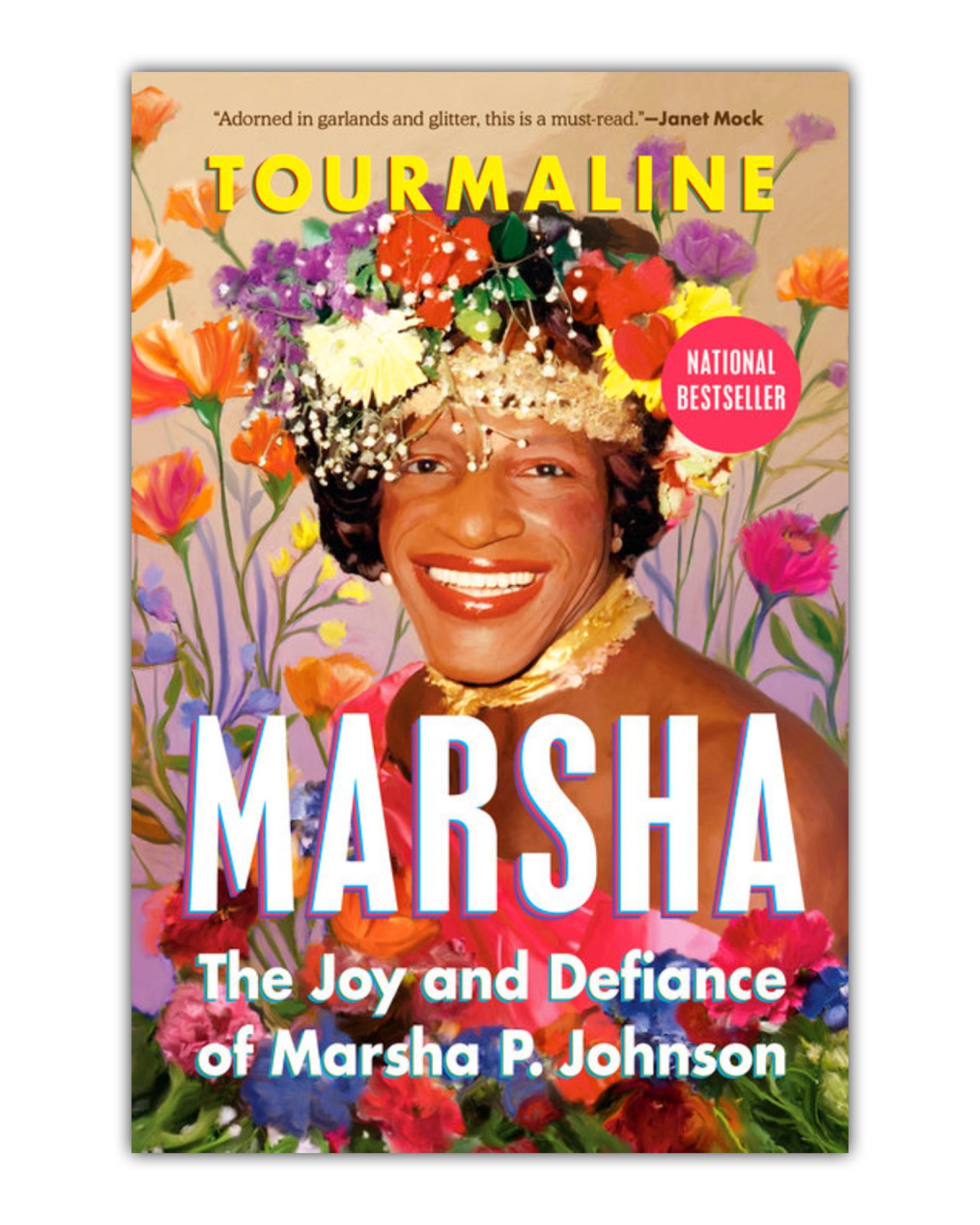

Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson

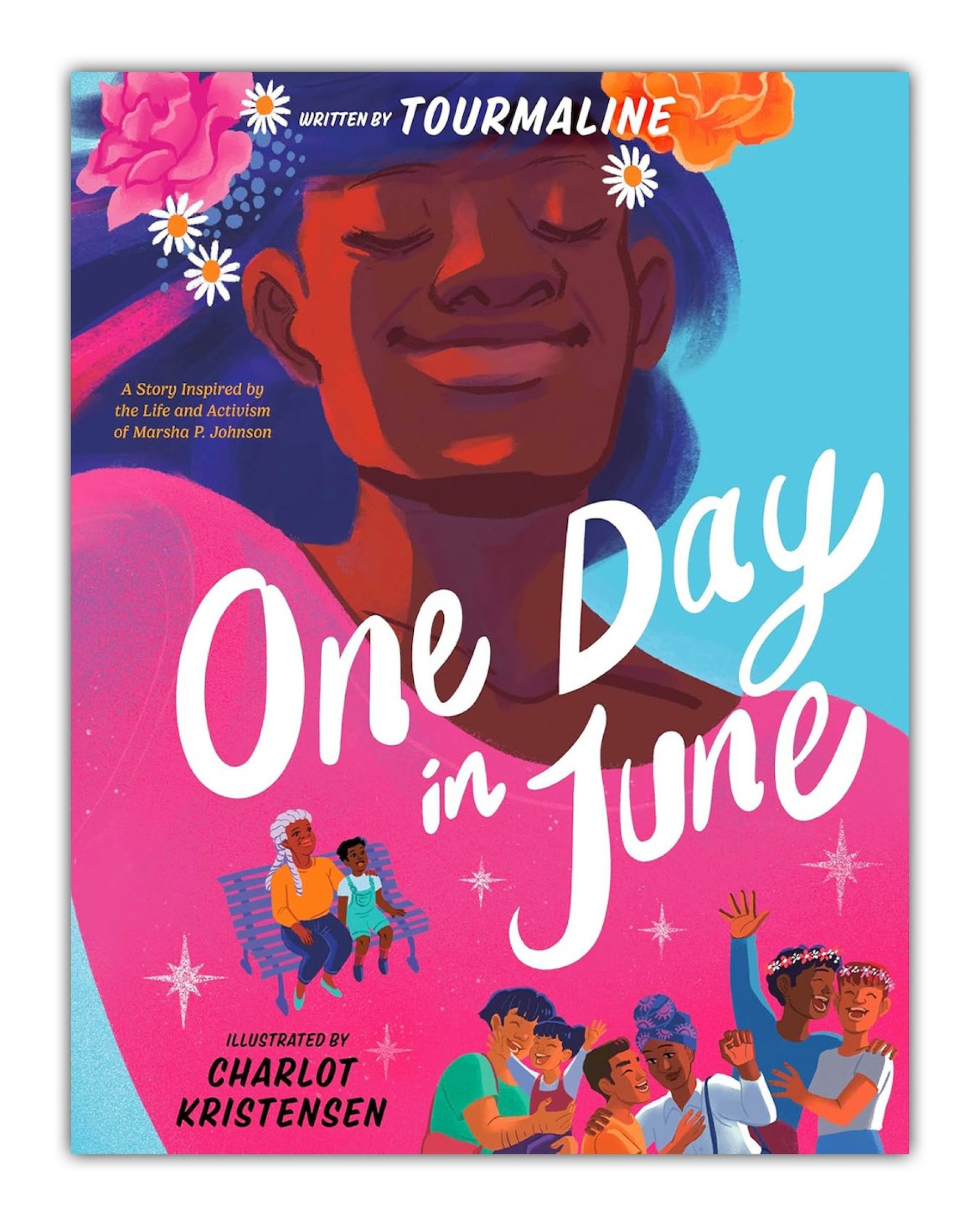

One Day in June

Boston Art Review Issue 15

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith

In Conversation, 2020–2021: Dialogues with Artists, Curators, and Scholars

B. Ingrid Olson: History Mother, Little Sister

Renée Green: Pacing

Tony Cokes – If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late: Vol. 1-3

Anna Oppermann: Drawings

Liz Magor: BLOWOUT

What Ever Happened to New Institutionalism?

Candice Lin: Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping (Out of Stock)